When one reads Science Fiction there is hardly anything so fascinating and yet so frustrating as the 'Time Travel' story. Fascinating, because it often explores the question 'what would things have been like if...?" or "if one could change a small thing like the position of a grain of sand would that have large effects in the future?". These questions are at the heart of personal or historical regret. Suppose Hitler were never born. Would this be a better or worse world today? Would it be a different world 100 years from now or would the forces of history push towards a singular result?

The stories are often frustrating due in part to a vaguely spelled out theory of time which often allows events that are confusing, contradictory and paradoxical. A science fiction story should not leave us with more questions than it resolves. For a reader of Fantasy, this may be acceptable, for Fantasy is not supposed to be taken as explanatory, prophetic or possibly realistic. But a good science fiction story should have explanations that are not incoherent and if in the story there is something which is claimed to be impossible, then there should be an explanation for that also.

At the heart of the problem is the 'Time Travel paradox' which goes something like this. Suppose a person travels to a time before she was born and breaks a causal chain that led to the traveler's birth. This problem has been commonly explored by asking 'What if you killed your own grandmother before she first conceived?' (Curiously the problem is never expressed in terms of killing your own mother). The apparent paradox is then of a logical sort: P entails NOT P and NOT P entails P. If you kill your grandmother then you would not be born, which in turn would bring it about that you not travel into the past, thus you would not kill your grandmother, thus you would be born causing you to again travel into the past to kill your grandmother.... ad infinitum.

The presupposition of almost all time travel stories is that each point along a time line is in some sense existent now, even the future points. This provides a conceptual basis for allowing us to visit a time point in the same way that we might visit a space point in ordinary experience. Einstein may have reinforced our comfort with this view by taking seriously the notion of time as another dimension very much like the spatial dimensions we are already familiar with.

There are several different standard attempts to resolve or avoid the paradox. The most standard is to ignore it. By sending someone far enough into the past, we do not know what influence that person will have and thus for all we know the person caused the world as we know it today. Another way to avoid the paradox is to state up front that we cannot change the past. There are different versions of this thesis. One is that we can go back and participate in a past causal chain but only in the way that already happened and the other way is to go back merely as an observer.

Some stories entertain the notion that you can go back and change things, but not those things that would lead to paradox. I would like to put forth the view that there is something wrong with all of these approaches and that the only view which is successful at resolving the paradox is an alternate universe theory of time travel which we shall explore momentarily. Such a view was expressed in "The Terminator" in which a character from the "future" confesses that maybe he just comes from a "possible future " not the actual future of this time.

When a time travel event occurs, it is helpful to see that it may be one of two kinds. Take, for instance, a "traveling" from time point c to time point b, where c is later than b. Either we are sending an object to a time and place where it already was and it is the same object in every respect as that object in that time and place or we are sending it to a place that it wasn't or at least wasn't in that exact state. Let us consider the second possibility first.

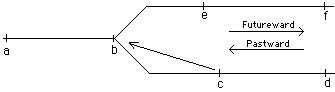

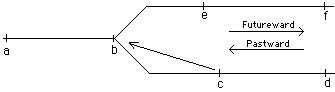

Supposing that the object wasn't at b but we intend to send it there anyway. If we are successful then we have created a contradiction, for it becomes clear that when the time travel event occurs it becomes true that the object was at time point b and yet it was false that the object was at b. This is an impossibility if we take any standard linear view of time. The most minimal means to accommodate this contradiction is to allow a timeline where the statement that the object exists at b is true and another timeline where the statement that the object exists there is false (the 'original' timeline.). In other words a timeline branching event has occurred. Any story that holds that the object was not on the timeline and now it is, is minimally committed to this branching universe concept. See Figure A...

This does not mean that a story must subscribe to the view that there are two existent timelines or Universes. The story may hold that the "original" time line b-c-d no longer exists, if it ever did and so even though we may conceptually represent the time travel event as above, some may claim that b-c-d no longer exists.

This way of talking about the time travel event makes it look as if 'first' the universe was linear, and then as soon as time point c arrived the universe became more complicated. But this way of describing it makes it sound as if there is a time when the object was not at b and then there is a time when the object was at b. What kind of time is this? It seems that we may express the same concept by noting that the object at c is the cause of the branching of timelines at b.

My position is that any coherent time travel story may be accommodated with the above diagram. There are various positions one could take regarding the existent or non existence of these time line segments that will provide the accommodation. We may even find it important to relativize existence to each point. For instance, we may imagine a story that claims that from the viewpoint of a person at point e timeline b-c-d does not exist. We can also image that there might be 4 possible stories about a person at time point a. The story may claim that for that person b-c-d exists but not b-e-f, or vice versa, or that both exist. One might even claim that time-travel has rendered neither existent, although this story might not be the common one. (There was a Fredric Brown story that had this as a punchline)

Although relativation of existence to positions on the timelines is not my favorite way of displaying these notions it at least allows for the description by a person at e that b-c-d used to be existent but now it isn't. This might only mean that for a person at a, bcd is existent but for a person at e, bcd is not existent.

This branching universe notion even accommodates the time traveler who cannot change the past, for such a view can be expressed by saying that bcd is always identical with bef. But such a story must in order not to be self contradictory only send objects to places where they already were, otherwise we risk having it be true that an object was there and at the same time be false. A writer cannot have it both ways. She cannot make a change in the time line and then insist that there is and always was only one timeline. A contradiction is not to be tolerated in a science fiction story since it breaks down the credibility that a science fiction story needs to not be merely fantasy.

The first thing we should note is that there is no paradox within the above understanding of time. If a traveler from point c returns to space-time point b where she did not exist before and causes a branching she then proceeds to travel down the new branch bef (unless another time travel event occurs). She is now free to bring about the non-existence of her analogous self on time line bef. If she does succeed in interrupting the causal chain that as analogous to the one that happened on line bcd that brought about her own existence and if this results in the non existence of her analogous self then of course her analogous self will not journey into the past causing another split in time. This in no way affects the existence of the traveler who left time point c, only the possible development of her analogous self.

In fact, it may be conceptually messier if she allows her new self to take a similar trip, for if this continues, we might see an infinite number of branchings at point b each caused by an analogous self traveling into the past. This is not a serious problem, its just messy. There are other conceptual problems in time travel stories that should be addressed, namely the problems of associated with rewriting history.

In so many stories, the traveler goes to a place in the past so as to change some event that will alter the future. This was the job of the terminator in Terminator 1. His task was to kill the mother of his enemy before she conceived. But now let us ask "what would this accomplish" According to our model, the terminator, if successful, travels from c to b and kills his enemies mother. The terminator then proceeds to lead a quiet little life on time branch bef. But has he changed the place from whence he came? If we hold that both timelines are equally existent then it seems that the entities that sent the terminator at best only created an alternate universe where their enemy doesn't exist. The original timeline will proceed as it would without change except for the loss of one terminator who has left to occupy an alternate time line. It is hard to imagine the motivation of these entities in the future to create such branching events since from their viewpoint all they have accomplished is getting rid of a well trained killing machine that was on their side.

To increase the stakes in such a story we somehow must conjecture that there is only room for one timeline, which is to say that timeline bcd or some portion of it becomes non existent and is replaced by the new timeline with the analogous beings.

So we have the view that first time proceeds down path abcd and then it later gets replaced with path abef. So in terms of figure A, the time between a to b is always existent. The time between b and c exists earlier but becomes non existent, and the time between b and f becomes existent. Something like this view seems to be present in most of these stories.

It may be that the viewpoint of the author is that bc stays existent and what disappears is the time line cd. Either of these views gives the beings on timeline bcd something to worry about because either their whole existence will be replaced with analogous beings or their world after the traveler leaves from c will be erased, in which case their future has been eliminated.

The primary problem with asserting that the time between b and c becomes non existent is that from the viewpoint of someone on the timeline bef, a possibly crucial change in history was made by an entity which was created by things that never existed and never will exist. So some existent things are causally brought about by non existent things. If a story is committed to this view, then reality becomes filled with possibly existent objects that under certain circumstances enter into causal chains and affect the actual world. This view does damage to what we usually think of as existence. That is, we would usually subscribe to the notion that anything that enters into a causal chain with the real world is part of the real world, i.e. existent. I would wish to reject this view and would propose that we grant the existence of any world or timeline that causally affects our world.

Some may object that sometimes non existent things do affect existent ones. My vision of a freer society in the future may affect the future. But it important to note that my vision of a freer society is not caused by the freer society but by my vision and my vision is existent.

But let us overlook this problem of causality associated with this non existence for a moment and ask a few more questions. If time travel is understood by those with the time travel device, what is their motivation for wanting to eliminate their own timeline and replace it with another one with analogous beings on it? They might believe that the other world is a better world and thus they are willing to be destroyed to have the world replaced. In this case their altruism is to be commended.

Or maybe they believe that by destroying this world, their essence of being is transferred to those analogous beings, except for the time traveler of course, for there could be two of her on the new timeline. The time traveler and her counterpart should be regarded as similar but not the same being. Furthermore, beings that exist in the first timeline but not in the second would not be transferred. But I think we should realize that this breaks again with the notion of science fiction and enters into fantasy unless the writer is willing to supply us with scientific reasons why such a "soul transfer" happens.

Another question we may ask within this view of one timeline being replaced by another is at what point does it happen. The standard view, which seems totally incoherent, is that it happens when the traveler makes the important change. But we have seen that an important change is made when the traveler first arrives at b. This is the first moment when the world is different than it once was. This is the moment where the timeline splits. If the view of those trying to change the past is that the world as they know it becomes non existent, then there is only one time that should mark the termination of their timeline, the moment that the traveler leaves on her trip, time c. Thus it makes no sense for another traveler after time point c to go back and "prevent the change", since all the time on timeline bcd has become non-existent when c occurred. This unfortunately happens in too many stories, i.e. Timecop, terminator, etc.

Sometimes I think the writers of such stories are deliberately unclear on their theory so that they can get away with more. But maybe in many cases the writer hasn't thought the idea out clearly enough to understand it herself. I am not asking that the writer build a time machine but only that they have some clear idea of what it is supposed to do.

If we take my view, that if time travel is possible and changing the past is possible then both timelines are equally exist, we have lost many of the standard motivations for going into the past, but not all. For instance, suppose you believed that this world is much worse off than it would have been if, say, the atomic bomb were not invented. Suppose you believe that with a time machine you would have the ability to change a sequence that led to the development of the atomic bomb. You could then go back and make the change, and after such change proceed into the future along timeline bef. This would be the world without the bomb, if you had done your work correctly. You could now live there, although it might be a little crowded with the two of you, unless you can convince the other of you to build a time machine and leave.

The people that you knew would still be back on the other time line.

Maybe similar ones would be on your new timeline, maybe they wouldn't,

but you couldn't go home again. Or could you?

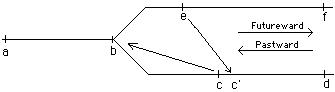

What conceptually would prevent the development of a inter-timeline

travel device? Nothing really. So, for instance, after your work is done

you may decide to move back to a time right after you left. See figure

B

A semantical problem becomes apparent. You tell your friends about your time travel venture and how you changed the past. Should they believe you? No. Nothing has changed. The past is still as it was. The atomic bomb still exists. But the problem is in the language. In a sense you did not visit your own past, but instead a past similar in every respect except for one thing, you were there. From that point the universes diverge and you are in a place even less like your own past. So, should we call this time travel or is it more appropriate to call it timeline creation or alternate timeline visitation?

It does have some resemblance to time travel as we usually think of it, though. For instance, if you didn't affect things too much you could go back and confirm or disconfirm historical records. The extent to which you did affect events would be the extent to which you couldn't be sure that that is really the way it happened on your original timeline. For my part, it seems to be enough like visiting another time so that it does not seem inappropriate to call it "time travel".

All of the considerations here are equally applicable to time travel events with mental objects instead of physical ones. For instance, suppose you wished to correct a regrettable action. Some stories may hold that you could transfer your mental makeup into an earlier self and do something different. But if by doing so, things become different than they originally were then a timeline split again is the result and the most we can say is that you have moved to the timeline where your regrettable action did not take place. The people on the new timeline will not blame you for your mistake, but the people on your original timeline still do. In the writing of the story, it would be interesting to wonder if this timeline move should be enough to get rid of your regret, since you still remember what you did on the home timeline.

Most of our discussion has been about time travel events that change the timeline, but let us for a bit consider stories where the traveler is sent to a place and time where she originally was. These stories usually have the traveler going into the past and then we later confirm the event by discovering some evidence of her existence at that past time. (Somewhere in time seemed to be such a story. I would like to argue that this is not an example of a science fiction story but instead represents a fantasy. I have several reasons for this position.

Suppose a traveler is sent to yesterday, to a place where it was noted that this traveler appeared. Upon her appearance, we started taking notes of exactly how she moved, when she stood up, when she sat down, when she raised a hand and what she said. In this story, let us give all of this information to the traveler before she is sent. Now let us look at the story from the traveler's point of view.

She arrives and she knows exactly what she is going to do. She cannot move in anyway different from what she knows she is going to do. In every respect she is a person trapped in an uncontrollable body. What is the explanation for this? Why can't she move contrary to what she knows will be the case. Why can't she cause a time branching event? The story owes us an explanation and if it is a science fiction story it cannot just be "well, that's the way it originally happened" In science fiction we need some hint at the force that is making it come out that way. How are we to explain the lack of will? Is it the Gods forcing her to do it? Fantasy. Is she just a passive rider in the body? Then who is making her body move the way it does?

Maybe, every time we send someone back, they lose their memory and thus they do what they would naturally do with no feeling of force. If this is true, we need an explanation for why the memory disappears, and the explanation should not be that this solves the problem of free will. As fantasy, this would be acceptable, but in science fiction we should receive an independent explanation.

In many of these stories, the traveler only partially knows the future and every attempt to change it usually ends up part of the fulfilling of the future instead. Are we to imagine that every time travel event happens in this way? If so, then they cannot be the result of a scientific device that makes time travel happen.

Let me give an example. Let us with our time travel device send an object, a marble, from 12:05 P.M. to 12 noon. First of all, we should only send this marble after we notice that it appears, otherwise we know that such an experiment is bound to fail. So we wait until 12 to see if it appears. Sometimes when we do this experiment it does appear and sometimes it doesn't. What determines when it does, some scientific principle? After we understand this principle we should be able to make it work every time just by being in accordance with the principle.

So it appears in front of us. Now let us suppose that at 12:01 we decide to not send the marble. Can we do that? If not why not? Is it a scientific principle or is it the gods again. If the latter, then we do not have a scientific time travel device but one that is dependent upon the mystical forces of the universe.

Another consideration is brought about by asking the question: "Is it really the same marble?". After all, some very accurate dating device, maybe like carbon dating, would show that the object that left was 5 minutes older than the object that arrived. If they were the same object, then the object that arrived would be a few moments older than the object that left. But we can see that this is impossible. Are we to image that there is some force that makes the marble younger as it goes back in time, just to make things work out? Again it appears the mystical forces are at work.

Instead of deciding not to send the marble back, let me propose a different experiment. Let us take the marble that appears at noon and make that the object that we send back. It disappears at 12:05 as planned. Questions arise. Where did this marble come from in the first place? This question will not get a satisfactory scientific answer, not even a satisfactory pseudo-scientific answer. It cannot be in terms of how the time travel device works. Again the answer must lie with mystical forces.

So the conclusion is that time travel of the sort, where the object is sent to a place that is identical to where it was, is not of the sort that science could claim credit for. Thus, it could not be a main subject of a science fiction time travel story. It might do well in a story of fantasy. And I say this without any derogatory implications about fantasy. I enjoy a good fantasy as much as the next person, but we should realize that in a fantasy many questions of explanation are inappropriate, but in a science fiction story they are quite at home and indespensible.

So now let us suppose that we are conducting our life in an ordinary way when all of a sudden a being who claims to be from the future materializes in front of us. How should we interpret the meaning of this phenomenon?

To back up a bit, we should realize that such an experience is conceptually possible, especially if we state the description of it in subjective terms. "It seems that someone has suddenly appeared out of nothing. He claims to be from the future." It is even possible that he believes he is from the future. Now let us suppose that we believe he believes he is from the future, and furthermore, he shows us how to create some technology that, as far as we know, has not been invented yet. All of this experience is not conceptually impossible, but now it is up to us to figure a reasonable interpretation for it.

Suppose furthermore, for some reason we decide that the explanation we are willing to consider does not involve alien deception, our hallucinations, our dreaming, some mind controlling experience implants, etc. In fact, let us say that we are only willing to consider two explanations. First, that he is from the future, our future, the way it is going to be and there is no way to change it, or he is from our future the way it would have been if he hadn't come back and caused a timeline split. If it is the second then we merrily proceeding down the path bef of make our future. (While our counterparts, who did not experience the appearance of the traveler are moving down the original path bcd to bring about the beginning of the traveler's journey).

I would like to suggest that the way we decide to interpret such an event will depend upon to what extent we believe the universe is subject to mystical forces verses so-far-undiscovered-scientifically-explainable forces. In other words, is this witnessed event the result of our world behaving like a fantasy or behaving more like science fiction?

If we choose the first, we may very well think of the traveler coming from our future and this future cannot be changed. If he furthermore tells us that we are all going to raise our hands in 5 seconds and even though we try not to we do anyway, then we would have confirmed that mystical forces our governing the situation. There would be no problem of free-will since, the fates will have rendered free-will an illusion. Furthermore, it would probably render the notion of explanation also one of illusion.

But if we are committed to the notion of explanation, we must interpret the apparent event as one with a scientific explanation (maybe not explicit), leaving enough order in the universe to render explanation meaningful. Then we can regard ourselves as free to use the information the traveler provides us to change our future to our liking. If the world that (s)he came from is undesirable and (s)he gives us the information necessary to change it then there is nothing except for the natural forces already in play to prevent us from doing so.

So in conclusion, I would like to recommend to any Science Fiction writer that thinks (s)he is writing science fiction that that (s)he use the timeline branching framework, without which the author risks contradiction and thus incoherence. Furthermore, if the author wishes to claim that the future that created the traveler no longer exists in order to blow the mind of the reader with paradox, (s)he should realize that the source of the paradoxical feel of the story is this very claim. The reader can easily dismiss the mind-boggle feeling by noting that the author is committed to an awkward theory of existence.

So let us write good Science Fiction Time Travel stories, make them fun and exciting but please let's also make them understandable.